|

|

|

Buddhism: Beliefs and Teachings

There is a great variety of religious practices that are associated with the word Buddhism, but most take their source of inspiration to be Siddhartha Gautama, who lived and taught in northern India some 2500 years ago. After he was enlightened he became known as the Buddha, which is a title meaning 'the enlightened one' or 'the awakened one'. It is a title given to a being who has attained great wisdom and understanding through their own efforts

Lesson One: The birth of the Buddha and his life of luxury

|

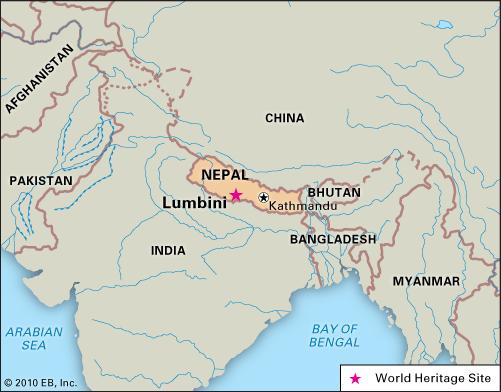

It is believed that Siddhartha was born around 500 CE in Lumbini in southern Nepal, close to the border with India. According to Buddhist tradition, Siddhartha was a prince: his father was King Suddhodana Tharu and his mother was Queen Maya Devi Tharu. The following traditional story is commonly told about Siddhartha's birth:

One night, Queen Maya had a dream that a white elephant came down from heaven and entered her womb. The elephant told her that she would give birth to a holy child, and that when he was born he would achieve perfect wisdom. About ten months later, when the baby was almost due, Queen Maya began the journey home to her parents' house, where she had planned to give birth. On the way she stopped in the Lumbini Gardens to rest and here she gave birth to a son. According to legend, he could immediately walk and talk without any support. He walked seven steps and with every step he took, a lotus flower sprang up from the earth beneath his feet. He then stopped and said, 'No further rebirths have I to endure for this is my last body. Now I shall destroy and pluck out by the roots the sorrow that is caused by birth and death.' He was called 'Siddhartha', meaning 'perfect fulfilment'. Shortly after Siddhartha's birth, a prophecy was made that he would become either a great king or a revered holy man. |

Siddhartha's mother died when he was just seven days old, and he was raised by his mother's sister, Maha Pajapati.

According to Buddhist tradition, Siddhartha grew up in a palace, surrounded by luxury. His father, Suddhodana, kept in mind the prophecy that was made about Siddhartha shortly after his birth. Suddhodana was determined that Siddhartha would follow in his footsteps and grow up to be a great king. So he decided to protect Siddhartha from any pain, sadness, disappointment or suffering that he might experience in his life. Suddhodana didn't want his son to seek religion and become a holy man. Suddhodana also thought that if his son became attached to a life of luxury, he would not want to leave the palace. Siddhartha was therefore supplied with everything he could possibly want. He wore clothes of the finest silk, ate the best foods, was surrounded by dancers and musicians, received an excellent education, and was generally cared for in every way Siddhartha later said of his upbringing: '' I was delicately nurtured ... At my father's residence lotus ponds were made just for my enjoyment: in one of them blue lotuses bloomed, in another red lotuses, and in a third white lotuses ... By day and by night a white canopy was held over me so that cold and heat, dust, grass, and dew would not settle on me. I had three mansions: one for the winter, one for the summer, and one for the rainy season. I spent the four months of the rains in the rainy-season mansion, being entertained by musicians, none of whom were male, and I did not leave the mansion. '' The Buddha in the Anguttara Nikaya, vol. 1, p. 145 Despite being spoilt and pampered while he was growing up, traditional stories say that Siddhartha was a good and kind person. At the age of 16 he married his cousin, Yasodhara. |

Lesson Two: The Four Sights

|

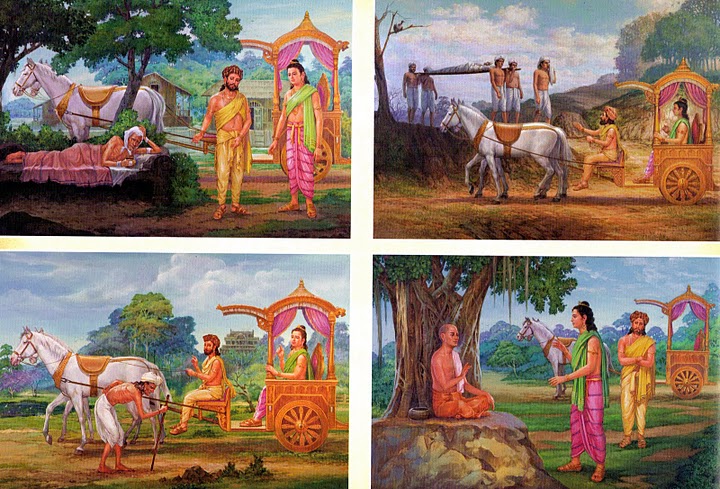

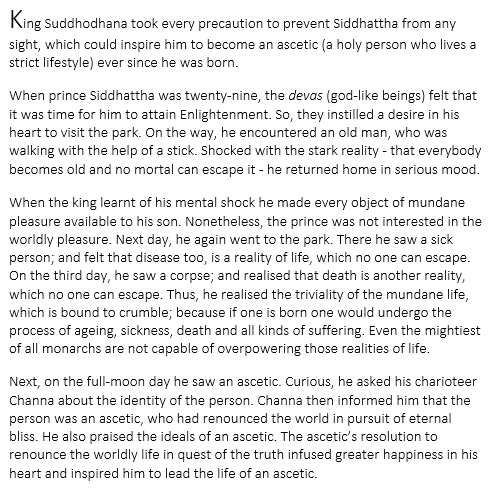

The first sight: old age

Siddhartha and Channa may not have gone very far before Siddhartha saw a frail old man, something he had never witnessed before in his life. He was shocked by what he saw as it was his first real experience of old age. The second sight: illness Some stories say that Siddhartha asked Channa to take him back to the palace, and he saw the other three sights on separate visits to the city. Other stories say that Siddhartha saw all four sights on his first and only visit to the city. Whether he made a number of trips or just one to the city, Siddhartha also saw someone lying in the road in agony. This disturbed him as he had never seen sickness or illness before, and he began to understand that illness was a reality of life. The third sight: death Siddhartha then saw a dead man being carried through the streets in a funeral procession. Some say that this third sight struck Siddhartha even more deeply. It was, after all, the first time he had seen death . He realised that death came to everyone. If someone was born, they would go through a process which would involve growing older, illness, suffering and death. There was no escape, even for kings. The fourth sight: a holy man The fourth sight Siddhartha saw was quite different. Walking calmly through the city was a man dressed in rags and carrying an alms bowl. The peaceful expression on the face of this holy man impressed Siddhartha very much. He felt inspired to be like this holy man and to become a wandering truth seeker. This was perhaps the beginning of Siddhartha's quest to search for the answer to the problem of why people suffer, and how to stop that suffering. |

We have seen that Siddhartha grew up in a palace living a life of luxury, shielded from the rest of the world. However, Siddhartha grew curious and wanted to explore outside the palace walls. Traditional Buddhist stories say that one day at the age of 29, despite his father's orders, Siddhartha decided to leave the palace grounds and go with Channa (his attendant and chariot driver) to the nearby city. Siddhartha then encountered the four sights, which had a profound effect on his life. The story of the four sights is recorded in Jataka 075.

Jataka 075

Leaving the palace

Finding the answer to the problem of suffering became the most important thing in Siddhartha's life. But he knew that if he stayed in the palace, he would find no answers. It is said that on the night his own son Rahula was born, he left the palace for good in search of an answer. He got up quietly, kissed his wife and newborn son, woke Channa, and they crept past the sleeping guards and silently rode away from the palace. When they both reached the edge of a river, they dismounted from their horses. Taking his sword, Siddhartha cut off his hair and swapped his rich clothes for the clothes of a beggar. He gave all his rings and bracelets to Channa to take back to his father. Channa watched as Siddhartha crossed the river and disappeared into the forest on the other side. By giving up his possessions and the symbols of his previous life, Siddhartha was letting go of the things that he thought were keeping him ignorant and thus resulting in his suffering. Later he was to teach that renunciation, a 'letting go', was important in reaching enlightenment. |

Test Yourself

'Seeing the four sights was the most important event in the Buddha's life' (12 marks)

'Seeing the four sights was the most important event in the Buddha's life' (12 marks)

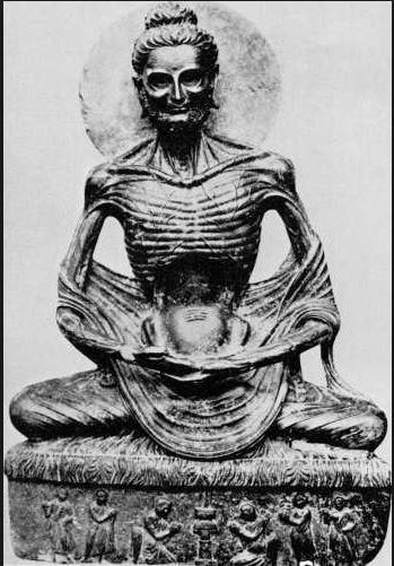

Lesson Three: The Buddha's ascetic life

Lesson Four: The Buddha's Enlightenment

|

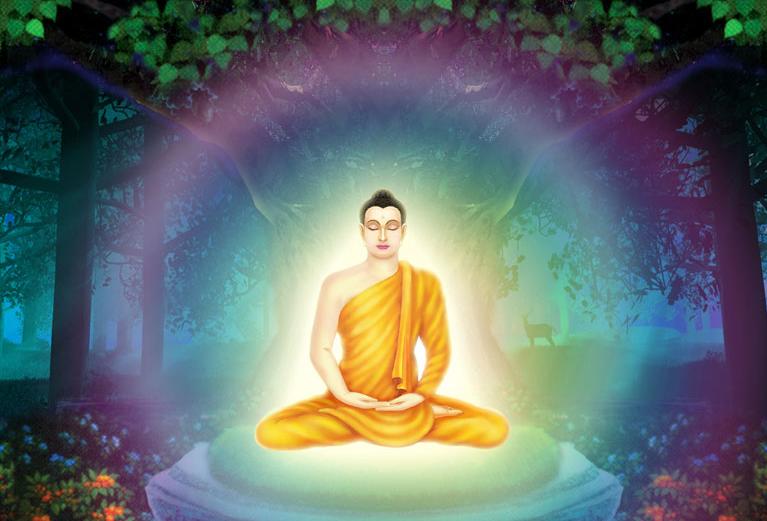

The Buddha's meditation

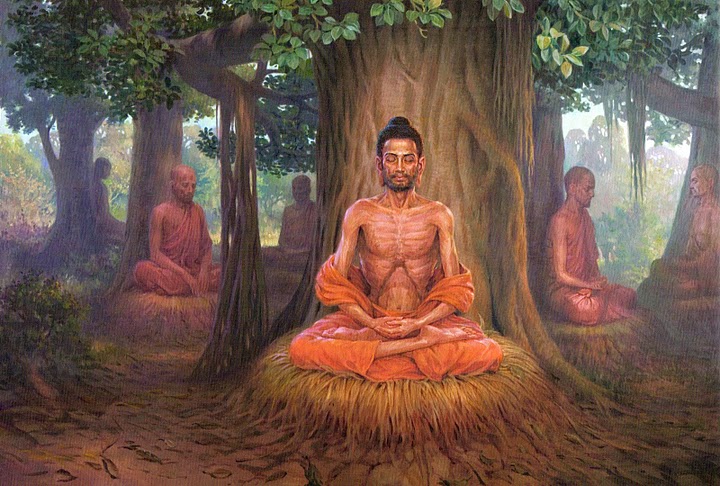

After rejecting his ascetic lifestyle, Siddhartha wondered if meditation might be a way of attaining the wisdom and compassion of enlightenment. Traditional stories say that he made himself a cushion of grass and found a suitable place to sit down and meditate, underneath a peepul tree. He sat with his face to the east and thought: '' Let only my sin, sinews and bone remain and let the flesh and blood in my body dry up; but not until I attain the supreme Enlightenment will I give up this seat of meditation. '' The Buddha in the Jataka, vol. 1, p. 71 Then Siddhartha began to meditate. Traditional stories tell how Mara, the evil one, appeared to try to stop him from achieving enlightenment. Mara tried a number of different tactics: • he sent his daughters to seduce Siddhartha • he sent his armies to attack Siddhartha • he offered Siddhartha control of his kingdom • Mara himself tried to attack Siddhartha. Throughout it all, Siddhartha stayed focused on his meditation. He ignored the temptations of Mara's daughters. Arrows directed at him from the armies turned to flowers before they could hit him. Towards the end of his meditation, Mara claimed that only he had the right to sit in the place of enlightenment and his soldiers were witnesses to this. He claimed that without anyone to witness his enlightenment, Siddhartha would not be believed. Siddhartha then touched the earth and called upon the earth to witness his right to sit under the peepul tree in meditation. The earth shook to acknowledge his right. There are different versions of the story of how Mara tried to stop Siddhartha from becoming enlightened. Most accounts are quite dramatic, but they all show that Siddhartha remained focused on his meditation, and that fear, lust, pride or other negative emotions were overcome with a disciplined mind. |

Becoming Enlightened

During the night that Siddhartha became enlightened, he experienced three important realisations. These realisations happened over three different periods (or (watches') during the night, and so they are known as the three watches of the night: • Firstly, Siddhartha gained knowledge of all of his previous lives. • Secondly, he came to understand the repeating cycle of life, death and rebirth. He understood that beings were born depending on their kamma (their actions), and he realised the importance of anatta (there is no fixed self). • Thirdly, he came to understand why suffering happens and how to overcome it. After his enlightenment, Siddhartha became known as (the Buddha', which means (the enlightened one' or (the fully awakened one'. The Buddha left the peepul tree and wandered back to the place where he had previously left the five ascetics, who were his first students. It is said that Mara still tried to tempt him further to keep his realisations to himself. But the Buddha was determined to teach about suffering and how to overcome it, to help others to achieve enlightenment. He asked anyone who would follow him to reject a life of extremism, which meant not having too many luxuries or living a very ascetic lifestyle. |

Lesson Five: The Dharma

|

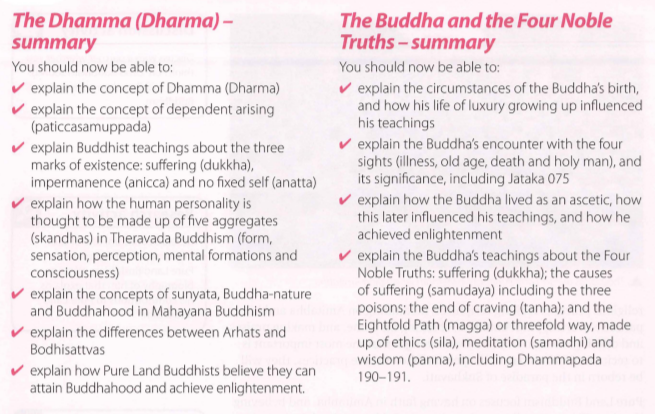

The term Dhamma (in Pali) or Dharma (in Sanskrit) has many meanings. It means the 'truth' about the nature of existence, as understood by the Buddha when he became enlightened. (His Four Noble Truths and the three marks of existence are examples of this.) It also means the path of training that was recommended by the Buddha for anyone who wishes to understand what he understood (for example, the Eightfold Path). It is sometimes translated as 'law', not in the sense of rules to be followed, but in the sense of a universal law such as Newton's law of gravity: a fact about the way things are.

Even though the Buddha described his insights into reality as the 'truth', he encouraged his followers to test his teachings against their own experience. He did not want people to follow his teachings unquestioningly because, for example, they were impressed with him as a teacher, or because he must be right if he had so many followers. In his book Old Path White Clouds, the Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh recounts stories about the Buddha's life. In one of them, the Buddha explains his teaching to the ascetic Dighanaka like this: '' My teaching is not a philosophy. It is the result of direct experience ... My teaching is a means of practice, not something to hold on to or worship. My teaching is like a raft used to cross the river. Only a fool would carry the raft around after he had already reached the other shore of liberation. '' Thich Nhat Hanh (Vietnamese Buddhist monk) Many Buddhists say that following the Buddha's teachings has relieved them of much suffering, giving them meaning, purpose and greater happiness or satisfaction in life. Becoming more aware, wise and compassionate is not only good for them, but also transforms their relationships with others and the wider world |

The Dhamma is also the second of the three refuges (also known as 'treasures' or 'jewels') in Buddhism. The other two refuges are the Buddha and the Sangha. Depending on the context in which it is used, Sangha has three different meanings: 1. all those who have become enlightened following the Buddha's teachings 2. monks and nuns 3. the community of all those who follow the Buddha's teachings, whether ordained or lay. In many traditions, it is common to recite the three refuges at the start of a Buddhist event or meeting, and in ceremonies where people become Buddhists. They might say: '' To the Buddha for refuge I go To the Dhamma for refuge I go To the Sangha for refuge I go '' To 'go for refuge' means to seek safety. For Buddhists, this means looking for safety from suffering. The Buddha taught that, a lot of the time, people take refuge in things which are unreliable and cannot provide lasting safety (for example, you get the new mobile phone you really wanted and you feel great about it-until it breaks or a new model comes out). However, following the truths and path of training he discovered would give lasting safety from suffering. When Buddhists take refuge in the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha, they are saying that they trust these things as lasting sources of safety from suffering. They are asking for the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha to guide them in their development of wisdom and compassion. When Buddhists 'go for refuge', they are expressing their longing for enlightenment, and their commitment to following the path leading to enlightenment. It is interesting to consider whether any of the three refuges could be said to be more important than the others. It could be argued that the Buddha is the most important because he provides an example for Buddhists to follow. If he had not discovered the Dhamma and then taught it, Buddhists might never have been able to understand the way out of suffering. On the other hand, it could be argued that the Dhamma is the most important because it describes the way things are. This 'truth' existed long before the Buddha recognised it (in the same way that the law of gravity is true whether anyone knows about it or not). Finally, the Sangha is very important to a Buddhist's life. For an ordinary person following the Buddha's teaching, it is very encouraging to know that other ordinary people have reached the wisdom and compassion of enlightenment, not just the Buddha. Nuns and monks (and other experienced teachers) are essential as guides to less experienced Buddhists. In Buddhists' everyday lives, the Sangha around them can also provide support, encouragement and friendship. |

Test Yourself

'The Dharma is the most important of the three refuges' (12 marks)

'The Dharma is the most important of the three refuges' (12 marks)

Lesson Six: The Concept of Dependent Arising

|

Dependent arising (paticcasamuppada) expresses the Buddhist vision of the nature of reality. It says that everything arises, and continues, dependent upon conditions. Nothing is permanent and unchanging. Dependent arising is often expressed in this simple formula:

• when this is, that is • from the arising of this, comes the arising of that • when this is not, that is not • when this ends, that ends. This basically expresses the view that life is an interdependent web of conditions. For example, a tree depends on soil, rain and sunshine to survive. Everything else also depends on certain conditions to survive. Nothing is independent of supporting conditions, which means that nothing is eternal, including human beings. Everything is a constant process of change. The Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of the Tibetan people, explained dependent arising like this: " All events and incidents in life are so intimately linked with the fate of others that a single person on his or her own cannot even begin to act. Many ordinary human activities, both positive and negative, cannot even be conceived of apart from the existence of other people ... in reliance upon the existence of others it becomes possible for the media to create fame or disrepute for someone. On your own you cannot create any fame or disrepute no matter how loud you might shout. The closest you can get is to create an echo of your own voice. " Tenzin Gyatso (the Dalai Lama)

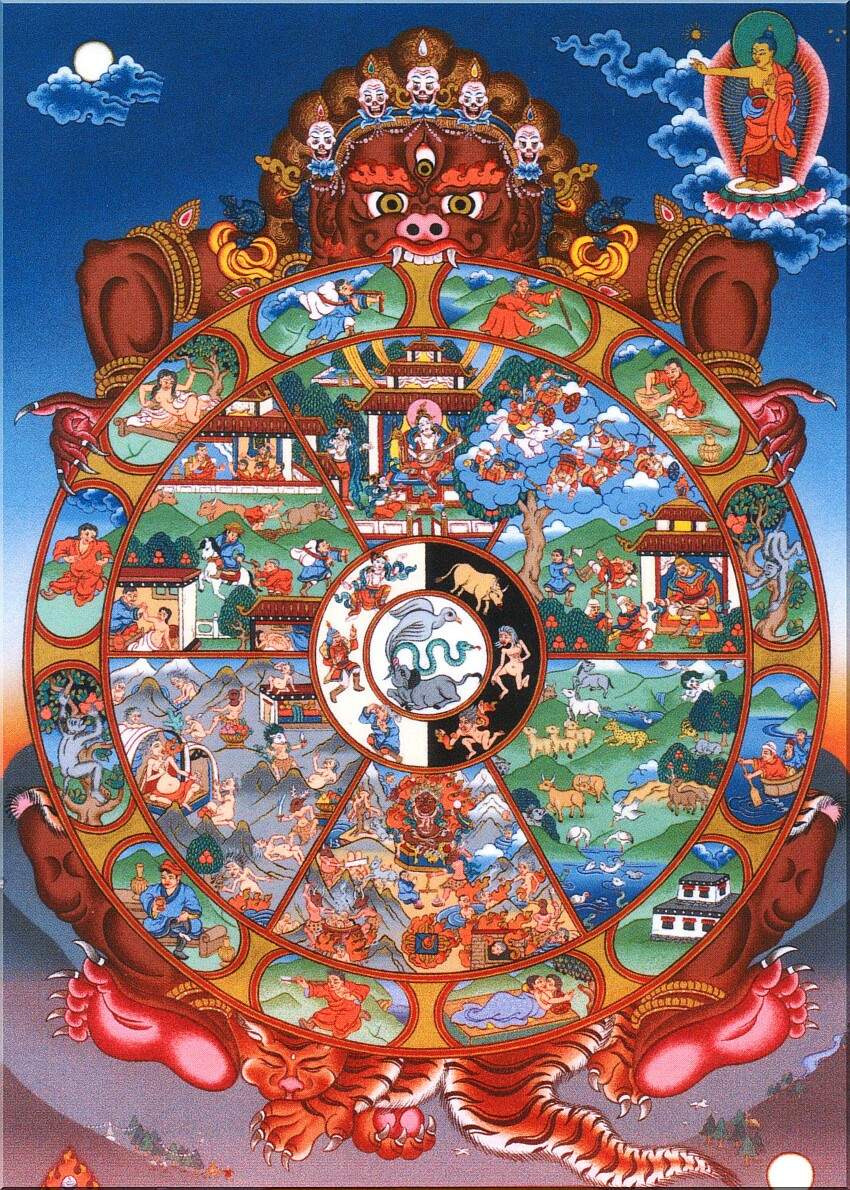

|

The Tibetan Wheel of Life illustrates the process of dependent arising in relation to human life, death and rebirth. The outer circle of the wheel is made up of 12links or stages (nidanas). The 12th link (old age and death) leads directly into the first link (ignorance). This represents the Buddhist teaching about rebirth: many Buddhists believe that when they die, their consciousness transfers to a new body. So the wheel shows the continual cycle of birth (and ignorance), death, then rebirth. This cycle is called samsara.

The type of world that a Buddhist is reborn into (for example, as a human, animal or heavenly being) is said to depend upon the quality of their actions (kamma) in their previous lives. The principle of kammasays that intentions lead to actions, which in turn lead to consequences. In the cycle of life, good intentions lead to good actions. Good actions can lead to a more favourable rebirth. Kamma is a specific example of dependent arising that explains how a person's actions create the conditions for their future happiness or suffering. For Buddhists, the ultimate aim is to break free of the cycle of samsara, because this is what causes suffering. The cycle is broken by following the Buddhist path but, more specifically, through breaking the habit of craving (tanha). For this reason, Buddhist practice focuses on the relationship between feeling and craving. When someone has an unpleasant feeling, they want to escape it, and when they have a pleasant feeling they become attached to it. Buddhism teaches that this kind of automatic response is what leads to suffering. Through breaking this response, and coming to understand the Buddha's teachings in other ways as well, Buddhists may achieve nibbana: a state of liberation, peace and happiness. |

Lesson Seven: Three Marks of Existence

|

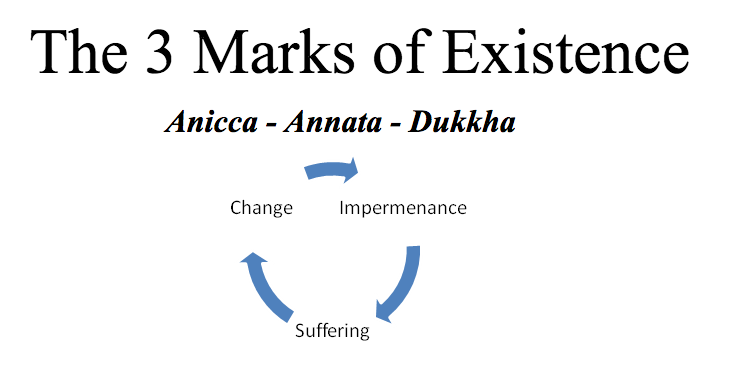

Buddhism teaches that there are three characteristics that are fundamental to all things. These are:

1. suffering (dukkha) 2. impermanence (anicca) 3. having no permanent, fixed self or soul (anatta) For Buddhists, understanding these three characteristics as part of life is important for achieving enlightenment. Anicca

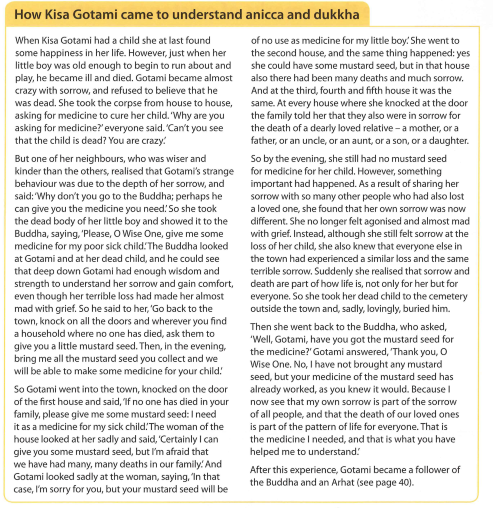

Anicca is usually translated as impermanence. As we have already seen, the Buddha taught that everything is impermanent and continually changing. Anicca can be thought of as affecting the world in three different ways: 1. It affects living things. For example, birth is followed by growth and then decay and finally death. Imagine for instance a small seed growing into a giant redwood tree. 2. It affects non-living things. For example, an iron nail that is left out in the rain will rust; a temple will eventually erode and turn into ruins if it is not repaired. 3. It affects our minds. Our thoughts, feelings, morals, longings and ideals change frequently throughout our lives. How Anicca and Dukkha relate to each other Even though things in the world change all the time, people often expect them to stay the same and the Buddha believed that this is one of the reasons why people suffer. He taught that when people expect things to remain unchanged, they become attached to them. Therefore when they do change (anicca) people experience suffering (dukkha). Buddhists believe that accepting that all things change -including themselves-will lead to less suffering. For Buddhists, the ultimate goal is to break the cycle of samsara and achieve nibbana, a permanent state of no suffering. Anatta

In Buddhism, the concept of anatta was developed in contrast to the belief in a soul or unchanging self. Anatta is often translated as 'no self', but it does not mean that Buddhists believe there is no concept of 'I', 'me' or 'self', just that the self is not fixed or permanent. The Buddha taught that there is no fixed part of a person that does not change. '' If all the harm, fear, and suffering in the world occur due to grasping on to the self, what use is that great demon to me? '' Shantideva (Indian Buddhist monk from the eighth century) Nagasena and the chariot A story that is often used to illustrate the concept of anatta is found in a text called 'The questions of King Milinda'. King Milinda was a Greek king who lived some 200 years or more after the Buddha. One day a monk called Nagasena arrived at the court of King Milinda. The king asked Nagasena what his name was. The monk replied that he was known as Nagasena, but that this was merely his name, without any reference to a real self or person. The king was confused by this and asked how there could be a person before him, who was standing in robes and was hungry for food, if Nagasena was just a name. Nagasena replied in what might be seen as a strange way. He asked the king how he had arrived today. The king said that he had arrived by chariot. Nagasena asked him to point out what a chariot was, which the king did. Nagasena then said that a chariot is not the wheels or the axle or the yoke, but is actually something separate to these things. So, the term 'chariot', like the term 'Nagasena', is merely a name used to refer to a collection of parts. Nagasena said that people are made up of various body parts like liver, kidneys, lungs and so on, but only when these are put together in a particular order and given a name do we recognise the 'owner' of these parts. A chariot exists but only in relation to its parts; likewise a person exists but only in relation to the parts they are made up of. There is not a separate 'self' that is independent from these parts. |

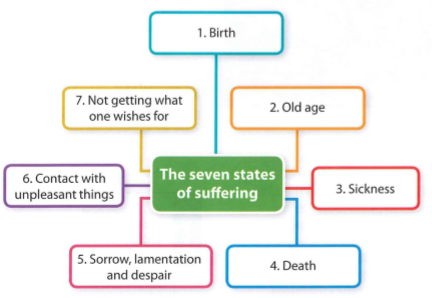

Dukkha

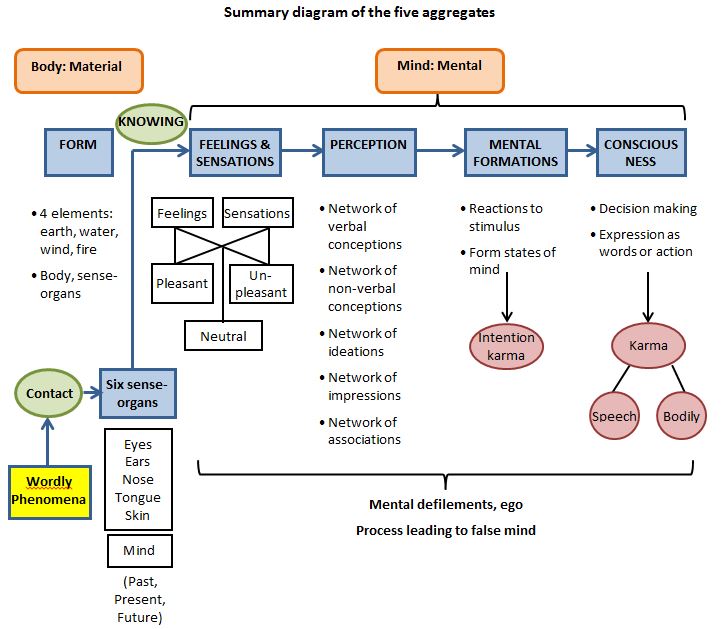

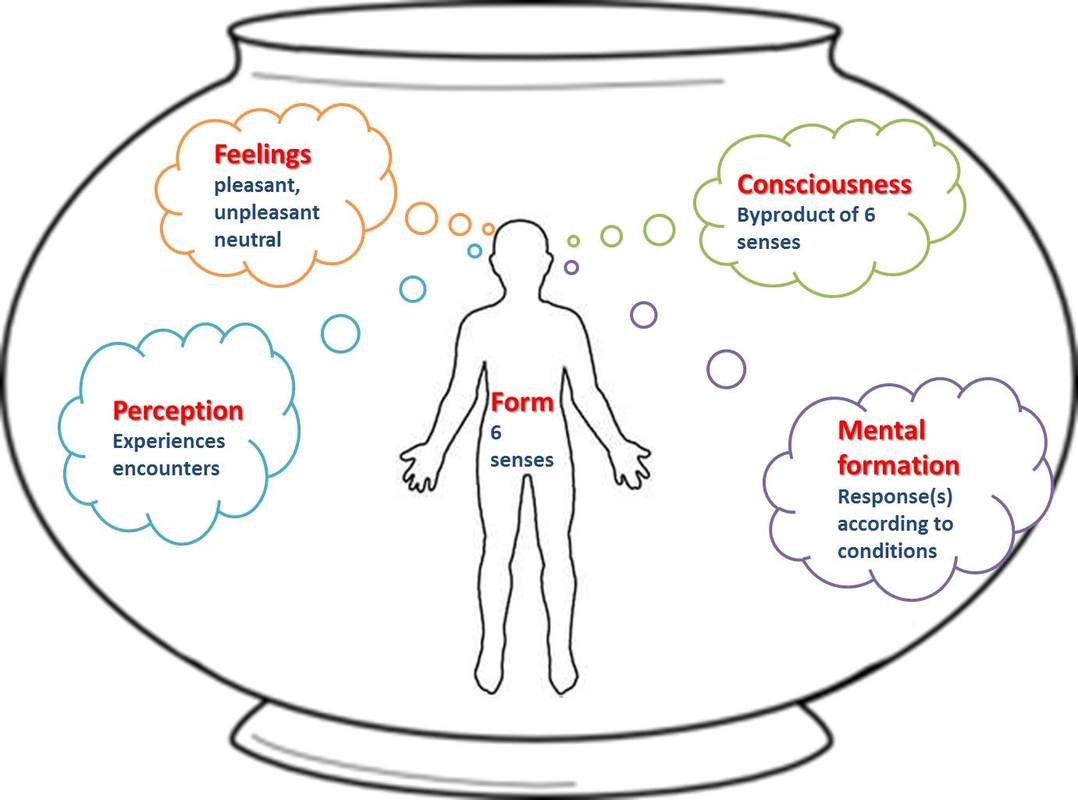

Dukkha is a fundamental concept in Buddhism. It has many different meanings but is best translated into English as suffering, dissatisfaction or unsatisfactoriness. Buddhists try to reduce suffering for themselves and others through right actions and intentions, and by gradually increasing their understanding of reality. Eventually they hope to break the cycle of samsara and achieve nibbana. The main reason why the Buddha left his life of luxury in the palace was to search for an answer to why people suffer. After the Buddha became enlightened, he gave a sermon in the Deer Park at Sarnath (a city in India). He spoke of the seven states of suffering. The first four of these (birth, old age, sickness and death) refer to the suffering caused by samsara, while the other three refer to further types of suffering that people experience in their lives. Different types of dukkha Suffering The first type of dukkha (called dukkha-dukkhata) refers to ordinary pain or suffering. It is used to describe both physical and mental (emotional) pain. Examples might include breaking a leg, getting the flu, being separated from and missing someone you love, or being upset at not achieving a goal. Change Another type of dukkha (viparinama-dukkha) is produced by change. One of the Buddha's teachings is that nothing is permanent- things are always changing. These might be small changes (such as the weather turning cloudy), gradual changes (such as getting older), or larger changes (such as moving to a new city). When something changes and a sense of happiness is lost as a result, this is viparinama-dukkha. It refers to the sorrow and unhappiness that a person feels as a result of a change or losing something good. Viparinama-dukkha can also be experienced during something good, as a subtle sense of unease and sorrow that comes from knowing the good thing won't last. Therefore, even happiness can be seen as dukkha. Attachment The third type of dukkha (samkhara-dukkha) is linked to the idea of attachment. Buddhism teaches that everyone is attached to other people, objects, activities and many other things. But when people crave and try to hold on to the things they are attached to, they suffer. This is perhaps the hardest form of dukkha to understand. It is often described as a more subtle dissatisfaction with life. Unlike dukkha-dukkhata and viparinama-dukkha, it may not arise due to specific events (such as twisting an ankle or ending a relationship). It is more to do with a general dissatisfaction with life that arises from many things, including the unhappiness that comes from change and from craving things that are not possible to have. The five Aggregates (Skhandhas)

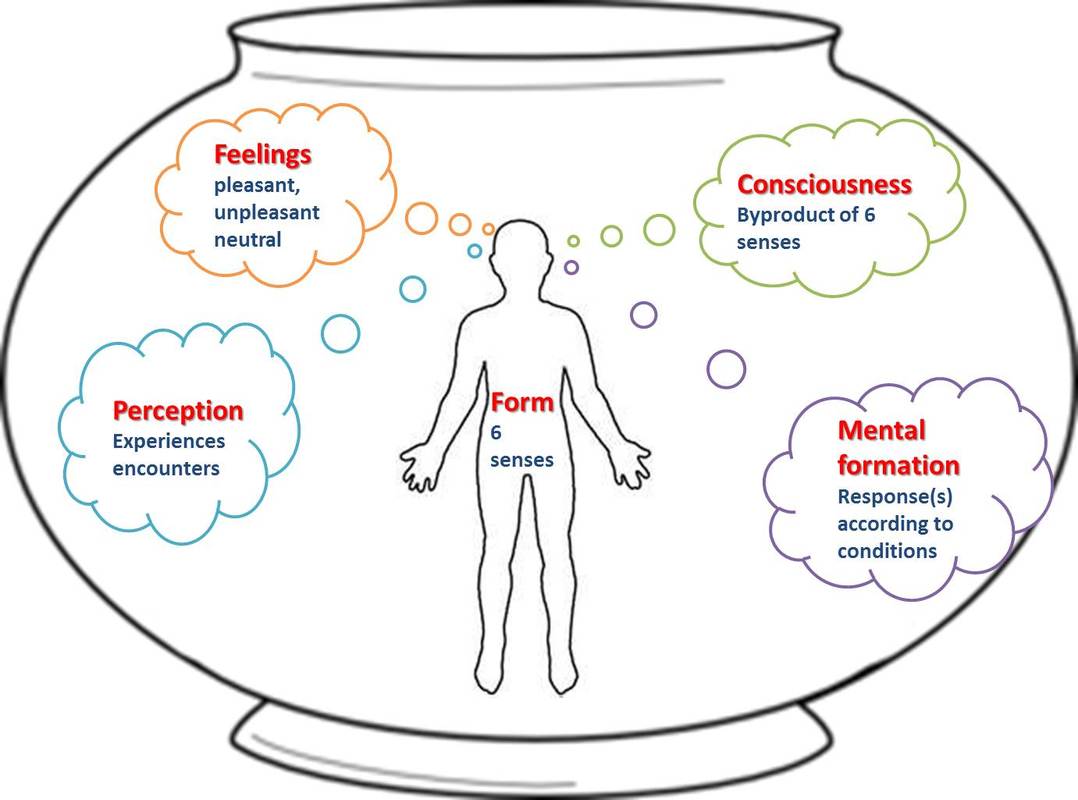

The Buddha taught that people are made up of five parts. These are called the five aggregates (skandhas). They are: 1. Form (our bodies) 2. Sensation (our feelings) 3. Perception (our recognition of what things are) 4. Mental formations (our thoughts) 5. Consciousness (our awareness of things) The Buddha said that these parts are constantly changing. Therefore the 'self' - which is the sum of all these parts- is also constantly changing. According to Buddhist teaching, death is followed by rebirth. But if there is no fixed, independent 'self' or 'soul' then what is reborn? How is someone's identity taken forward into their new body? For Buddhists, the answer is that there is a continuation of kammic energy, which means that the energy that is a person's kamma passes on into another being. |

Test Yourself

'The idea that people consist of five aggregates is the most useful Buddhist teaching to help explain the concept of Anatta' (12 marks).

'The idea that people consist of five aggregates is the most useful Buddhist teaching to help explain the concept of Anatta' (12 marks).

Lesson Eight: The Four Noble Truths

|

The Four Noble Truths are often said to contain the essence of the Buddha's teachings. They were discovered by the Buddha while he searched for enlightenment under the peepul tree. They were also the first teachings that he gave to the five ascetics, during his first sermon in the Deer Park at Sarnath.

The Four Noble Truths are: 1. the truth of suffering ( dukkha) 2. the truth of the cause of suffering (samudaya) 3. the truth of the end of suffering (nirodha) 4. the truth of the path leading to the end of suffering (magga). Another way of thinking about these four truths is to say that: 1. suffering exists 2. suffering is caused by something 3. suffering can end 4. there is a way to bring about the end of suffering. Therefore, the Four Noble Truths seek to explain why people suffer and how they can end that suffering. The First Noble Truth

The first noble truth draws attention to the fact that suffering is a part of life and something that everyone experiences. The Buddha taught that there are four unavoidable types of physical suffering: birth, old age, sickness and death. Everyone experiences these in the course of their life. Buddhism teaches that beings will experience these four types of suffering many times over a number of lives, as part of the cycle of samsara. Remember that old age, sickness and death were three of the sights that the Buddha saw when he first left the palace. Coming into contact with these types of suffering had a profound effect on him and prompted his search to find an end to suffering. The Buddha also taught that there are three main forms of mental suffering: separation from someone or something you love; contact with someone or something you dislike; and not being able to achieve or fulfil your desires. '' Now this, [monks], is the noble truth of suffering: birth is suffering, aging is suffering, illness is suffering, death is suffering; union with what is displeasing is suffering; separation from what is pleasing is suffering; not to get what one wants is suffering; in brief, the five aggregates subject to clinging are suffering. '' The Buddha in the Samyutta Nikaya, vol. 5, p. 421 Even though the Buddha taught that it is important to recognise that suffering is a part of life, he did not deny that happiness exists. He often acknowledged in his teachings that there are many different types of happiness that everyone can experience. However, as we saw on page 21, the Buddha taught that even though happiness is real it is also impermanent; it will not last and will therefore eventually give way to unhappiness. Some people think that the Buddha's teaching that suffering is a part of life, and that happiness doesn't last, is a negative or pessimistic way to view life. Buddhists, however, would argue that it is simply realistic. They would argue that everyone experiences pain and suffering at some point in their lives. It is a universal truth, meaning that it affects everybody. So dissatisfaction or suffering in life is a problem that everyone needs to overcome. Buddhists reflect on suffering not to make themselves miserable, but to be able to release themselves from that suffering. Many people try to combat suffering with temporary pleasures. To take one simple example, imagine that you got a bad mark for an exam and feel miserable about it as a result. You eat a bar of chocolate to cheer yourself up, but the happiness that the chocolate creates only lasts until you get to the end of the bar. It doesn't solve the root cause of your unhappiness. Because happiness and pleasures are temporary, the Buddha did not believe they could be the ultimate answer to the problem of suffering. Instead he developed other teachings and advice to help prevent people from suffering because of their dissatisfaction with life. As part of this he taught that the first step to end suffering is to accept the first noble truth: that sufferingi s an unavoidable part of life. Buddhism teaches that one of the ways in which suffering may be reduced is to not personalise it. Suffering simply happens, and the key to reducing it is to not become 'attached' to it. If a person puts themselves at the centre of the suffering, the suffering becomes worse because it is personalised. This is how Ajahn Sumedho wrote about suffering: '' The ignorant person says,'l'm suffering. I don't want to suffer. I meditate and I go on retreats to get out of suffering, but I'm still suffering and I don't want to suffer ... How can I get out of suffering? What can I do to get rid of it?' But that is not the First Noble Truth; it is not: 'I am suffering and I want to end it: The insight is,'There is suffering' ... The insight is simply the acknowledgment that there is this suffering without making it personal. '' Ajahn Sumedho (American Buddhist monk) The Third Noble Truth

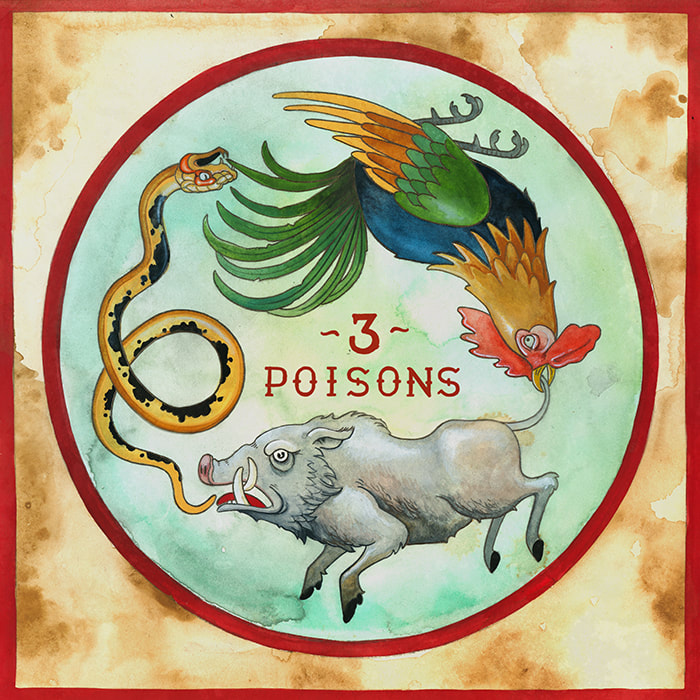

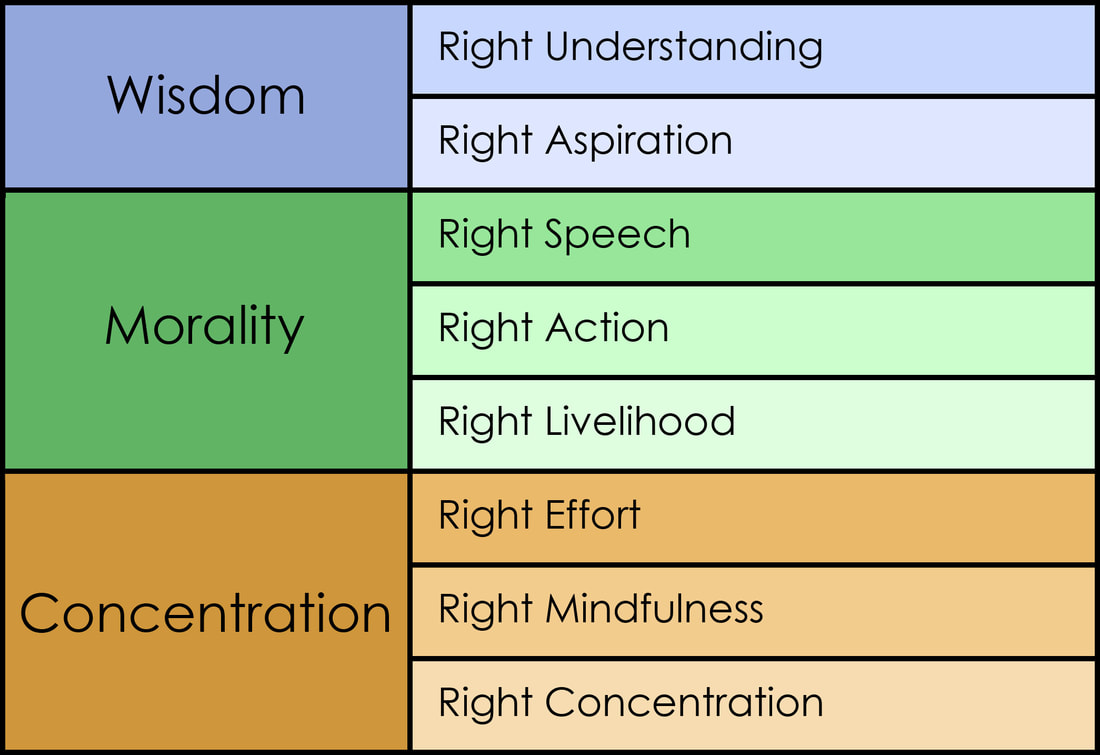

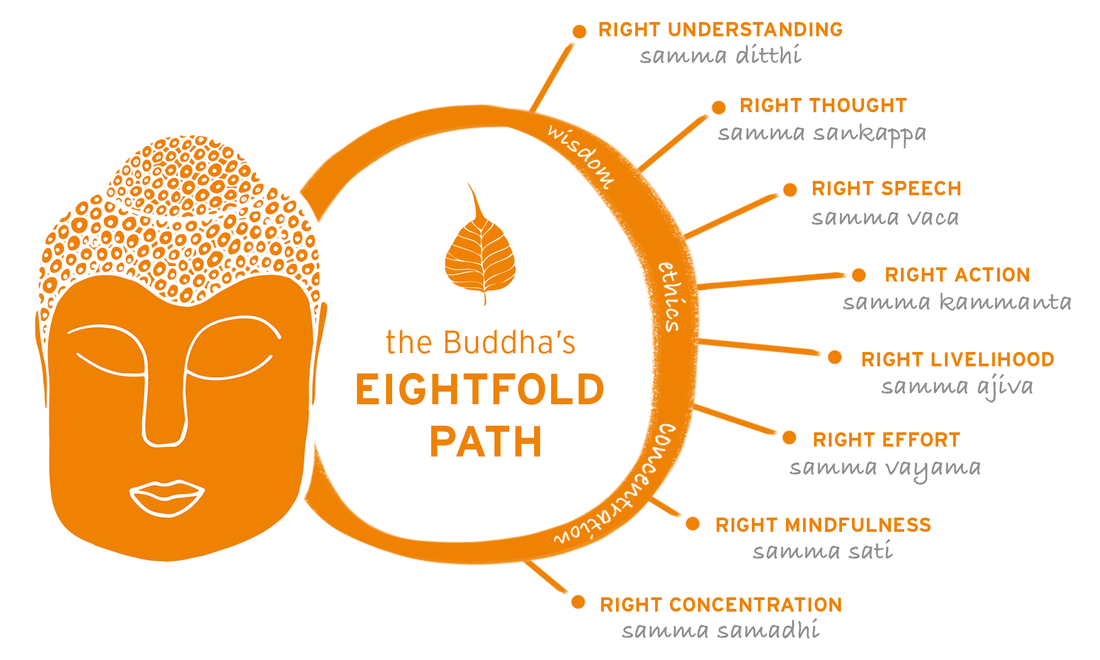

The third noble truth (nirodha) is that there is an end to suffering. This means that Buddhism teaches it is possible to end a person's suffering through their own actions and efforts, and that this can lead to enlightenment. Buddhists believe that the Buddha achieved this, and that anyone else can achieve it too. This noble truth is important because it teaches that it is possible to achieve happiness, and that although suffering is an unavoidable part of life, it is also possible to overcome it On the previous page we saw how the second noble truth teaches that one of the main causes of suffering is craving things. It follows then that if people stop craving things, their suffering will cease, and this is the message of the third noble truth. The Buddha taught that when people desire things but don't get them- or can't hold on to them for long enough -they become frustrated and unhappy with life. So they have to let go of this craving in order to stop feeling dissatisfied with life. The Buddha said that this does not mean that people should avoid the things they enjoy or crave. In fact, this might only make things worse, because they might end up craving something more if they can't have it at all. Instead, the Buddha taught that people should enjoy and take pleasure in things but recognise that they can't last. People should enjoy things without craving them or becoming too attached to them. The Buddha also taught that the way to stop craving is to have an inner satisfaction with life and a total appreciation of what one has already got. '' Now this, [monks], is the noble truth of the cessation of suffering: it is the remainderless fading away and cessation of that same craving, the giving up and relinquishing of it, freedom from it, non reliance on it. '' The Buddha in the Samyutta Nikaya, val. 5, p. 421 Buddhists believe that it is important to overcome ignorance as well as craving in order to end suffering and achieve enlightenment. The third noble truth, therefore, teaches that it is possible to end suffering, and that this can be achieved by overcoming ignorance and craving. The fourth noble truth gives specific steps to help Buddhists attain this goal. Interpretations of Nirvana and Enlightenment. 'Nirvana' literally means the 'extinction' or snuffing out of a flame- in this case, the extinction of the three poisons (or three fires) of greed, hatred and ignorance. The Buddha said after his enlightenment that he knew he was now entirely free of these three poisons. 'Bodhi' literally means 'knowing'. A Buddha is 'one who knows' the truth about the nature of existence. Such a person would know exactly what causes suffering, and have no expectations of permanence. Knowing this, they would naturally behave according to the five moral precepts, which are a description of the perfect wisdom and compassion of a Buddha. But did the Buddha know everything? Buddhists have discussed this question over many centuries. Most Buddhists would probably say they believed the Buddha knew everything about the principles governing the nature of existence, such as the three marks of existence and Four Noble Truths. They would not say he knew absolutely everything, because that would mean believing he had supernatural powers. The Eightfold Path consists of the following eight practices, which are grouped below into the three different sections that make up the threefold way.

Ethics (sila) 1. Right speech: speaking truthfully in a helpful, positive way; avoiding lying or gossiping about others. 2. Right action: behaving in a peaceful, ethical way; avoiding acts such as stealing, harming others, or overindulging in sensual pleasures. 3. Right livelihood: earning a living in a way that does not harm others, for example not doing work that exploits people or harms animals. This section of the threefold way is concerned with having good morals and behaviour, and living in an ethical way. It essentially requires Buddhists to act in ways that help rather than harm themselves and others. Meditation (samadhi) 4. Right effort: putting effort into meditation, in particular thinking positively and freeing yourself from negative emotions and thoughts. 5. Right mindfulness: becoming fully aware of yourself and the world around you; having a clear sense of your own feelings and thoughts. 6. Right concentration: developing the mental concentration and focus that is required to meditate. This section of the threefold way is concerned with how to meditate effectively, which for Buddhists is an important practice for developing wisdom and achieving enlightenment. Wisdom (panna) 7. Right understanding: understanding the Buddha's teachings, particularly about the Four Noble Truths. 8. Right intention: having the right approach and outlook to following the Eightfold Path; being determined to follow the Buddhist path with a sincere attitude. This section of the threefold way emphasises the importance of overcoming ignorance and achieving wisdom, to truly understand the Buddha's teachings and thus the nature of reality. For Buddhists, developing this understanding is essential for achieving enlightenment. '' Mental phenomena are preceded by mind, have mind as their leader, are made by mind. If one acts or speaks with an evil mind, from that sorrow follows him, as the wheel follows the foot of the ox ... If one acts or speaks with a pure mind, from that happiness follows him, like a shadow not going away. '' The Buddha in the Dhammapada, verses 1-2 Despite being called a 'path', the Eightfold Path is often represented as a wheel with eight spokes. This emphasises the fact that the different steps do not need to be followed in a linear sequence, one after the other, but can be practised at the same time. Each of the different steps reinforces the others. For example, acting more ethically might include making the effort to meditate more regularly. This leads to a greater understanding of the Buddha's teachings, which in turn makes it easier to act more ethically and meditate more effectively, which further increases one's wisdom, and so on |

The Four Noble Truths in practice

'' The truth of suffering is like a disease, the truth of origin is like the cause of the disease, the truth of cessation is like the cure of the disease, and the truth of the path is like the medicine. '' The Visuddhimagga, p. 512 In his teaching of the Four Noble Truths, the Buddha can be compared to a doctor. When a doctor establishes that you have an illness, he first finds the cause of the illness (the first two noble truths). He then tells you what the cure is (the third noble truth). He then prescribes the cure, and undergoing this treatment helps you to get better (the fourth noble truth). '' Each of these truths entails a duty: stress [suffering] is to be comprehended, the origination of stress abandoned, the cessation of stress realized, and the path to the cessation of stress developed. When all of these duties have been fully performed, the mind gains total release ... Thus the study of the four noble truths is aimed first at understanding these four categories, and then at applying them to experience so that one may act properly toward each of the categories and thus attain the highest, most total happiness possible. '' Thanissaro Bhikkhu (American Buddhist monk) Buddhists aim to come to a complete understanding of these four truths through study, reflection, meditation and other activities. For Theravada Buddhists, understanding the four truths is the most important goal for achieving enlightenment. Mahayana Buddhists likewise believe the Four Noble Truths are very important, but they also emphasise other teachings, such as the development of compassion, as being central to the experience of enlightenment The Buddha taught that the 'cure' to overcome suffering is the Eightfold Path. This is a series of practices that Buddhists follow in order to achieve enlightenment. The second noble truth

The second noble truth (samudaya) explores the origins of suffering. Buddhists believe that understanding why people suffer is important if suffering is to be reduced. The Buddha taught that one of the main causes of suffering is tanha, which means 'thirst' or 'craving'. This refers to wanting or desiring things. The Buddha said that there are three main types of craving: 1. Craving things that please the senses, such as beautiful sights or pleasant smells. One example is drinking a hot chocolate not because you are thirsty, but because you like the taste of it. 2. Craving to become something that you are not, such as craving to become rich or powerful or famous. 3. Craving not to be, or craving non-existence. This refers to when you want to get rid of something or stop it from happening any more, such as not wanting to feel embarrassed after making a mistake, or not wanting to feel pain after twisting an ankle. '' Now this, [monks], is the noble truth of the origin of suffering: it is this craving which leads to renewed existence, accompanied by delight and lust, seeking delight here and there; that is, craving for sensual pleasures, carving for existence, craving for extermination. '' The Buddha in the Samyutta Nikaya, vol. 5, p. 421 Buddhism teaches that the reason why people find life to be unsatisfactory and full of suffering is because they become attached to the things they like, and want to avoid the things they don't like. However, the concept of anicca (impermanence) teaches that everything changes. So if people become attached to things, when they lose them through change, they inevitably suffer. The temporary pleasures that people crave cannot last or make them feel consistently happy. Suffering and the three poisons At the centre of the Tibetan Wheel of Life there are usually three animals that represent three different tendencies: • a pig, representing ignorance • a cockerel, representing greed and desire • a snake, representing anger and hatred These are called the three poisons in Buddhism. They sit in the centre of the wheel because they are considered to be the forces that keep the wheel spinning, and the cycle of samsara turning. The Buddha taught that craving is rooted in ignorance. This is not the sort of ignorance related to not knowing the location of a country or not knowing how to speak a language, but a deeper ignorance about people, the world and the nature of reality. Buddhists believe they will only achieve enlightenment by overcoming ignorance and finding wisdom. The Buddha also taught that craving leads to greed and hatred. It is these three poisons that trap humans in the cycle of samsara and prevent them from reaching nirvana. Ajahn Sumedho's experience of how craving leads to suffering

Ajahn Sumedho, who was previously the abbot of the Amaravati Buddhist monastery in the UK, talks about his experience of how craving can lead to suffering: 'In my practice I have seen that attachment to my desires is suffering. There is no doubt about that. I can see how much suffering in my life has been caused by attachments to material things, ideas, attitudes or fears. I can see all kinds of unnecessary misery that I have caused myself through attachment because I did not know any better. I was brought up in America- the land of freedom.It promises the right to be happy, but what it really offers is the right to be attached to everything. Like every materialist culture, America encourages you to try to be as happy as you can by getting things. However, if you are working with the Four Noble Truths, attachment is to be understood and contemplated; then the insight into nonattachment arises. This is not an intellectual stand or a command from your brain saying that you should not be attached; it is just a natural insight into nonattachment or non-suffering: The Fourth Noble Truth

The fourth noble truth (magga) is the 'cure' to end suffering: a series of practices that Buddhists can follow to overcome suffering and achieve enlightenment. It is known as the middle path or middle way, because the Buddha taught that people should lead a moderate life between the two extremes of luxury and asceticism. He found that neither of these extremes was helpful in his search for enlightenment. The fourth noble truth is the Eightfold Path, which consists of eight aspects that Buddhists can practise and follow in order to achieve enlightenment. These eight aspects are sometimes grouped into three different sections: ethics, meditation and wisdom. Together these three make up what is sometimes known as the threefold way. '' But if any one goes to the Buddha, the Doctrine and the Order as a refuge, he perceives with proper knowledge the four noble truths: Suffering, the arising of suffering, and the overcoming of suffering, and the noble eightfold path leading to the cessation of suffering. '' The Buddha in the Dhammapada, verses 190-191 |

Lesson Nine: Theravada Buddhism

|

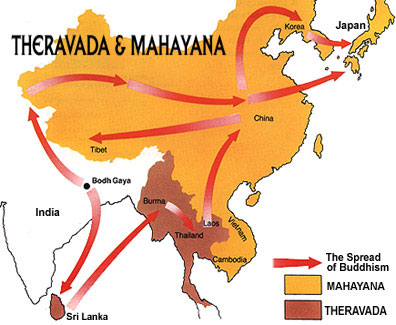

Theravada Buddhism is one of the oldest schools of Buddhism, and is known as 'the school of the elders'. (In Pali, which is the main language used in Theravada texts and chanting, 'thera' means 'elder' and 'vada' means 'school'.) Today, Theravada Buddhism is practised mostly in Thailand, Sri Lanka, Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar.

Theravada Buddhism is sometimes regarded as classical or orthodox Buddhism, with a high degree of uniformity in how it is practised. The school emphasises ordination in the monastic community. While some women have been ordained within Theravada Buddhism, full ordination is primarily reserved for men.

The Buddha is seen as the main focus of commitment and is one of the three refuges. He is a guide, an example for others to follow and a teacher, but he is not considered to be a god.

Theravada monastics devote their whole lives to following the path of enlightenment, and promise to follow a number of rules, including not to own anything, not to have any sexual relationships, and never to be offensive to anyone. Theravada monastics focus in particular on meditation. They believe that commitment to the Buddha and the Eightfold Path will bring good merit or karma. Their goal is to achieve enlightenment and reach nirvana. Some Theravada Buddhists believe it is possible to share their own good fortune with other people, by transferring the merit they have gained to someone else. This transfer of merit becomes particularly important when someone has died. When this happens, the family and friends may gather round whoever has died and transfer their merit to him or her, in the hope that this will help the dead person to have a favourable rebirth. (This practice is less common among Western Buddhists.) |

|

Here is a simple example to show how the five aggregates interact (all of these things happen more or less at the same time):

• Form: you enter a room and see a slice of cake (a physical object). • Sensation: seeing the slice of cake gives you a feeling or sense of anticipation. • Perception: you recognise that it's a slice of cake, from having seen other slices of cake in the past. • Mental formations: you form an opinion of the cake and decide whether you want to eat it or not • Consciousness: all of these things are connected by your general awareness of the world |

The Buddha taught that people are made up of five parts, called the five aggregates (skandhas). Theravada Buddhists in particular believe that these five parts interact with each other to make up a person's identity and personality.

The five aggregates are: 1. Form: this refers to material or physical objects (such as a house, an apple, or the organs that make up a person's body). 2. Sensation: this refers to the feelings or sensations that occur when someone comes into contact with things. They can be physical (such as a sensation of pain after tripping over), or emotional (such as a feeling of joy after seeing a friend). 3. Perception: this refers to how people recognise (or perceive) what things are, based on their previous experiences. For example, you might recognise what the feeling of happiness means because you have felt it before; you recognise what a car is because you have seen lots of other cars in the past. 4. Mental formations: this refers to a person's thoughts and opinionshow they respond mentally to the things they experience, including their likes and dislikes, and their attitudes towards different things. 5. Consciousness: this refers to a person's general awareness of the world around them. |

Lesson Ten: Mahayana Buddhism

|

Sunyata

An important concept in Mahayana Buddhism is sunyata, which is often translated as 'emptiness'. For Mahayana Buddhists, understanding sunyata is essential for achieving enlightenment. Sunyata could be understood as a restatement of anatta. It emphasises that not only do human beings not have a fixed, independent, unchanging nature, but that in fact all things are like that. Nothing exists independently but only in relation to, and because of, other things. A wave, for instance, cannot be separated from the sea. The example of the chariot helps to explain the concept of sunyata. For another example let's think about a computer. A computer does not have a 'soul' - a separate, independent bit that forms the essence of the computer. A computer is instead made up of lots of different parts, such as wires, a plastic case, a cooling fan, a graphics card and so on, which rely on each other and work together to form the whole computer. The computer relies on other people to make those parts and put them all together, and to keep them working. When the computer breaks down, it might be taken apart and bits of it reused to help repair other computers. This makes the computer interdependent and interrelated. It is also impermanent: the computer will eventually break down and stop working. For Buddhists, realising that everything depends on, and interlinks with, everything else can lead to trust, compassion and selflessness. Realising that everything is impermanent is important for reducing the suffering that results in becoming too attached to things. These realisations are important for achieving enlightenment. |

Mahayana Buddhism is a term used to describe a number of different traditions that share some overlapping characteristics. A few of the main traditions that come under the Mahayana umbrella are Pure Land Buddhism, Zen Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism and Nichiren Buddhism. Today, Mahayana Buddhism is mainly practised in China (including Tibet), Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, Mongolia and Bhutan.

Theravada Buddhists view the Buddha as a purely historical figure. They believe it is no longer possible to meet or interact with him in the world. In contrast, Mahayana Buddhists believe that the Buddha remains active and can influence the world. He can be encountered through visions and meditation, and he can manifest himself in many different forms, times and places. Theravada and Mahayana Buddhists emphasise different beliefs and practices. One difference is how enlightenment can be achieved. Buddha-nature is an important concept in some Mahayana traditions. At a basic level, it refers to the idea that everyone has the seed, even the essence (or nature) of a Buddha already inside them. Sometimes it is even said that, deep down, every person is already enlightened. But because a person's Buddha-nature is hidden by desires, attachments, ignorance, and negative thoughts, it is not realised. Only when people truly come to understand the Buddha's teachings- and therefore understand the nature of themselves and reality around them-do they experience the Buddha-nature that was always there.

One example given in traditional Buddhist scripture to help explain Buddha-nature is that of honey surrounded by many bees. The honey is sweet and tasty but as long as it is surrounded by bees, it isn't possible to get to the honey, even though it's been there all the time. The only way to experience the honey is to get rid of the bees. Mahayana Buddhists aim to achieve Buddhahood: to become a Buddha (an enlightened being). They believe that everyone has the potential to do this and to become a Buddha because of their inherent Buddha-nature. |

Test Yourself

'Explain two Mahayana teachings. Refer to scripture or sacred writing'. (5 marks).

'Explain two Mahayana teachings. Refer to scripture or sacred writing'. (5 marks).

Lesson Eleven: The Arhat and the Bodhisattva.

For Theravada Buddhists, an Arhat is a 'perfected person' who has overcome the main causes of suffering-the three poisons of greed, hatred and ignorance - to achieve enlightenment. When someone becomes an Arhat, they are no longer reborn when they die. This means they are finally freed from the suffering of existence in the cycle of birth and death (samsara), and they can attain nibbana. This goal is achieved by following the Eightfold Path and concentrating on wisdom, morality and meditation

During the Buddha's lifetime, many of his disciples became Arhats. Among them were the first five monks the Buddha was with and the Buddha's own father, Suddhodana.

" I have no teacher, and one like me

Exists nowhere in all the world ...

I am the Teacher Supreme.

I alone am a Fully Enlightened One

Whose fires are quenched and extinguished. ''

The Buddha in the Majjhima Nikaya, vol. 1, p. 171

Mahayana Buddhists sometimes use the term Arhat to refer to someone who is far along the path of enlightenment but has not yet become enlightened. However, for Mahayana Buddhists the ideal is to become a Bodhisattva rather than an Arhat.

A Bodhisattva is someone who sees their own enlightenment as being bound up with the enlightenment of all beings. Out of compassion, they remain in the cycle of samsara in order to help others achieve enlightenment as well. The ultimate goal for Mahayana Buddhists is to become Bodhisattvas.

Bodhisattvas combine being compassionate with being wise. Mahayana Buddhists believe that the original emphasis of the Buddha's teachings to his disciples was to 'go forth for the welfare of the many', and Bodhisattvas aim to do just this.

'' However innumerable sentient beings are; I vow to save them. " A Bodhisattva vow

A person becomes a Bodhisattva by perfecting certain attributes in their lives.

There are six of these that Mahayana Buddhists focus on (called the six perfections):

1. generosity- to be charitable and generous in all that is done

2. morality- to live with good morals and ethical behaviour

3. patience-to practise being patient in all things

4. energy-to cultivate the energy and perseverance needed to keep going even when things get difficult

5. meditation-to develop concentration and awareness

6. wisdom- to obtain wisdom and understanding.

Mahayana Buddhists believe there are earthly and transcendent Bodhisattvas. The 'earthly' ones continue to be reborn into the world, to live on Earth, while the 'transcendent' ones remain in some region between the Earth and nibbana as spiritual or mythical beings. However, they remain active in the world, appearing in different forms to help others and lead them to enlightenment. Mahayana Buddhists pray to these Bodhisattvas in times of need.

During the Buddha's lifetime, many of his disciples became Arhats. Among them were the first five monks the Buddha was with and the Buddha's own father, Suddhodana.

" I have no teacher, and one like me

Exists nowhere in all the world ...

I am the Teacher Supreme.

I alone am a Fully Enlightened One

Whose fires are quenched and extinguished. ''

The Buddha in the Majjhima Nikaya, vol. 1, p. 171

Mahayana Buddhists sometimes use the term Arhat to refer to someone who is far along the path of enlightenment but has not yet become enlightened. However, for Mahayana Buddhists the ideal is to become a Bodhisattva rather than an Arhat.

A Bodhisattva is someone who sees their own enlightenment as being bound up with the enlightenment of all beings. Out of compassion, they remain in the cycle of samsara in order to help others achieve enlightenment as well. The ultimate goal for Mahayana Buddhists is to become Bodhisattvas.

Bodhisattvas combine being compassionate with being wise. Mahayana Buddhists believe that the original emphasis of the Buddha's teachings to his disciples was to 'go forth for the welfare of the many', and Bodhisattvas aim to do just this.

'' However innumerable sentient beings are; I vow to save them. " A Bodhisattva vow

A person becomes a Bodhisattva by perfecting certain attributes in their lives.

There are six of these that Mahayana Buddhists focus on (called the six perfections):

1. generosity- to be charitable and generous in all that is done

2. morality- to live with good morals and ethical behaviour

3. patience-to practise being patient in all things

4. energy-to cultivate the energy and perseverance needed to keep going even when things get difficult

5. meditation-to develop concentration and awareness

6. wisdom- to obtain wisdom and understanding.

Mahayana Buddhists believe there are earthly and transcendent Bodhisattvas. The 'earthly' ones continue to be reborn into the world, to live on Earth, while the 'transcendent' ones remain in some region between the Earth and nibbana as spiritual or mythical beings. However, they remain active in the world, appearing in different forms to help others and lead them to enlightenment. Mahayana Buddhists pray to these Bodhisattvas in times of need.

Lesson Twelve: Pure Land Buddhism

|

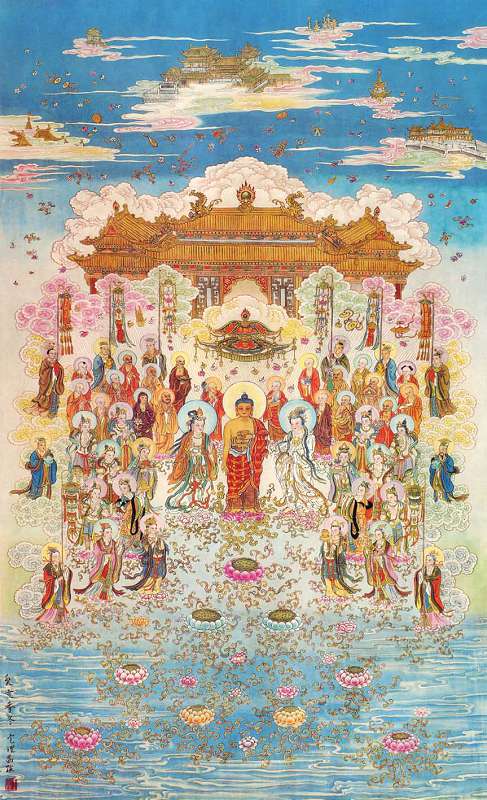

Pure Land Buddhism is part of the Mahayana tradition of Buddhism. It began in China as early as the second century CE, then developed and spread throughout China and into Japan. Today, Pure Land Buddhism is the main type of Buddhism practised in Japan.

Pure Land Buddhism is based on faith in Amitabha Buddha, in the hope of being reborn in the paradise where Amitabha lives. Amitabha was a king who renounced his throne to become a monk. Mahayana scriptures tell how when he achieved enlightenment and became a Buddha, he created a pure land called Sukhavati, which is a land that can be found far to the west, beyond the boundaries of our own world. Amitabha created this perfect paradise out of his compassion and love for all beings. Pure Land Buddhists believe that if they are reborn into this land, they will be taught by Amitabha himself and will therefore have a much better chance of attaining Buddhahood (becoming a Buddha). In the pure land, there is no suffering, and none of the problems that stop people in our own world from attaining enlightenment. '' [Sukhavati] is rich in a great variety of flowers and fruits, adorned with jewel trees, which are frequented by flocks of birds with sweet voices ... And all the beings who are born ... in this Buddha-field, they are all fixed on the right method of salvation, until they have won nirvana. For this reason that world system is called the 'Happy Land: '' The Larger Sukhavativyuha Sutra, sections 16-24 T'an-luan is considered to be the person who founded Pure Land Buddhism in China. He encouraged believers to follow five types of religious practice: reciting scriptures, meditating on Amitabha and his paradise, worshipping Amitabha, chanting his name, and making praises and offerings to him. Of these five he taught that the most important is to recite Amitabha's name. If a person follows these practices, they will be reborn in the paradise of Sukhavati. Pure Land Buddhism focuses on having faith in Amitabha, and believing that he will help Buddhists to be reborn in Sukhavati. Faith in Amitabha is more important than a person's own actions and behaviour. This is quite different to other schools of Buddhism. For example, Theravada Buddhism teaches that enlightenment can only be achieved through a person's own thoughts and actions, and they cannot rely on any outside help to achieve enlightenment. The fact that it is seen to be easier to reach enlightenment in Pure Land Buddhism, with Amitabha's help, has allowed this school of Buddhism to gain popular appeal. '' Even a bad man will be received in Buddha's land, how much more a good man? '' Honen (twelfth century Japanese Pure Land teacher) '' Even a good man will be received in Buddha's land, how much more a bad man? '' Shinran (a student of Honen) |

Test Yourself

'Pure Land Buddhism offers an easy way to gain enlightenment' (12 marks).

'Pure Land Buddhism offers an easy way to gain enlightenment' (12 marks).